An Exploration Into The Works Of Stanley Kubrick And Alfred Hitchcock

The Great British Film Director Stanley Kubrick

An exploration into the works of Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock

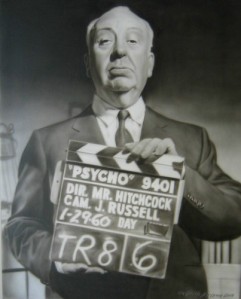

‘Stanley Kubrick is a talented shit’. Executive Producer Kirk Douglas, having somewhat hesitantly employed the little known director to direct his vision of Spartacus had been forced to eat humble pie and admit his admiration for the talent and creative vision of the young director. Meanwhile, audiences fuelled by incredulous hype flocked in their droves to see ‘Psycho’, considered by many as the most shocking motion picture of all time. The year is 1960.

In terms of modern cinema both Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock are held as luminaries of their profession. Their pictures’ have visually, socially and culturally influenced generations of movie – goers not to mention aspiring actors, writers and directors. With Hitchcock consistently referred to, as ‘The Master of Suspense’ and Kubrick an undeniable genius, their collective impact upon modern cinema could not have been greater. To fully understand their individual contribution to motion picture history we must examine their work.

The 1960’s marked a major change for American cinema; the collapse of the Hollywood Studio System led to a weakening of censorship laws. From virtual obscurity sex and violence moved to the forefront of mainstream cinema. Stanley Kubrick, handpicked to resurrect the floundering historical drama Spartacus, had acquired himself a reputation of a young man with a bright future, whilst with the release of ‘Psycho’ Hitchcock was taking full advantage of our changing social attitudes towards cinema and, after the successes of ‘Vertigo’ (1958) and ‘North by Northwest’ (1959), was at the height of his powers.

The films of Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock often focus on stories surrounding the darker sides of life. Kubrick chose to work in a variety of different genres, though all of his works have a distinctly morose undertone, whether it’d be the potential onset of nuclear war as in ‘Dr Strangelove’ or the post – apocalyptic world as portrayed in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ the once loving family unit breaking down in ‘The Shinning’ all portray a sense of inescapable doom. High tension, suspense and drama were the hallmark of a Hitchcock picture. Hitchcock’s films with the exception of ‘Under Capricorn’ (1949) all encompassed the same elements and very similar narratives, therefore always were categorized as thriller or horror pictures, a factor which lead to the director being labelled as ‘The Master of Suspense’.

Psycho, produced by Universal Studios and released through Paramount in 1960, contained a blatant depiction of sex and violence unlike any mainstream film that preceded it. It is known as Hitchcock’s anti romance picture as it tells the story of infidelity, fraud and cold-blooded murder, with a woman; so anxious to start a new life with her lover she steals 40,000 dollars from her employer. As the story progresses we see her guilt over her crime which eventually culminates with her decision to return the stolen cash. However, before she is granted the opportunity, an unknown assailant at the hotel she is staying, murders her, in horrific fashion. With the subsequent investigation of her demise, identification of her killer and reasoning behind this somewhat motiveless attack Hitchcock’s story evolves constantly keeping the audience hooked as they have no clue as to what will happen and are left breathless by the end.

Psycho included the first love scene between Janet Leigh (Marion Crane) and John Gavin (Sam Loomis). In the opening scene they are portrayed as lovers semi naked lying on a bed. Hitchcock’s reasoning for this being that he believed audiences to be much more sophisticated than in previous decades and a straightforward kissing scene would not suffice. He believed that you must honestly portray how people behave in an intimate moment. However, in 1960 this scene was considered highly controversial for its visual characteristics and sexual innuendo. The film itself also depicted two brutal murders in a fashion not seen before on screen, the most memorable being that of Marion Crane’s grisly demise at the hands of Norman Bates within the intimate and claustrophobic setting of a shower.

In order to secure a mainstream release Hitchcock had to fight to ensure the film was made as close to his vision as possible and thus had to figure out ways to work around the censorship laws. Hitchcock decided to shoot the entire movie in black and white knowing full well that the ‘shower scene’ would court instant controversy for being too grotesque and gory. In 1960 it was completely out of the question that a knife penetrate the victim’s flesh on screen. Hitchcock had to find ways of depicting the scene in such a fashion that the audience never view actual penetration of flesh but are in no doubt as to the scenario. Bernard Herrmann achieved this brilliantly through a score, which is quite possibly the most recognised in cinematic history. Hitchcock himself shot the structure of the scene through intelligent camerawork and employing a camera chopping technique merely suggested to his audience the events which had occurred, however by the time the murderer has fled the bathroom we are left in no doubt that he / she brutally stabbed Marion Crane to death despite never once viewing the knife penetrate flesh.

The movie itself also contained two of the most iconic visual characteristics in the history of cinema. The image of the Bates Motel is instantly recognisable within modern society. The house and hotel itself are ingrained in Hollywood legend with its visual impact influencing virtually every horror movie which required the image of a house, hotel or even dilapidated building to this very day. Additionally, the scene in which Marion Crane’s sister comes to the house to investigate her disappearance and discovers the decomposed body of Mrs. Bates in the basement is, without question, one of motion picture history’s most recognisable scenes. It is believed that Hitchcock placed ‘Mrs Bates’ in actress Vera Miles’ dressing room to test its ‘scare factor’. Suffice to say it achieved the desired effect.

It has been quoted that Hitchcock had a very bleak view on society, a factor that draws obvious association with his work. Often dealing with murders, the perpetrators and their consequences. Most of his characters lack sufficient moral fibre (the obvious example being Janet Leigh’s character in Psycho, Marion Crane), whom despite being fodder for Norman’s psychosis, is a woman of questionable morals as she is a thief and adulterer.

In Psycho, virtually every aspect of what an audience were used to in a narrative structure was challenged. Just as Hitchcock had violated Marion in the safety and intimate security of the shower, Hitchcock had violated the viewer. Audiences whom had come accustomed to the traditional narrative style were denied the comfort of associating themselves with the central character, Marion Crane and after her death were forced to align themselves with the murderer – Norman Bates.

Norman Bates gave audiences a portrait of the most disturbing screen figure yet. We learn, through the narrative and Anthony Perkins’ brilliant performance that he is a psychotic. Aside from his crimes there is little to distinguish him from other people. This factor is very unsettling as it implies there is a subculture of sadistic, perverted and psychotic people. Hitchcock raises the idea that despite the appearance of normalcy there are individuals in our society who have the potential to commit the most horrifying acts . this very concept was most shocking, as the killer was not presented as a monster or supernatural being, but a regular person.

‘Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest, most shocking mystery with a galaxy of stars’. This was one of the advertising slogans used to promote Psycho upon its release. Hitchcock was adamant Psycho appealed to a younger audience and commissioned a series of provocative posters to advertise his latest work. The more notorious examples were of Janet Leigh in scantily clad clothing and in images of the Bates Motel – a now iconic visual characteristic of motion picture history, with the petrified victim in the background. Hitchcock’s timing for the release of Psycho could not have been more opportune. In 1960 America cinemagoers were predominantly teenagers between the ages of 15 – 19 yrs old and through a well-calculated advertising campaign Hitchcock knew he could guarantee bums on seats. He also knew there was a current market for modern films and the ‘slasher’ film gave a clear picture of the changing sexual attitudes people felt towards cinema. The film became a social event not to be missed. Audiences bonded together having experienced this new tabooed experience of sexuality and violence. With the success of Psycho, production companies then gave the green light to a whole host of pictures where sexuality, violence and other issues were no longer considered taboo subjects to explore within cinema. The most noticeable being ‘The Graduate’ (1967), ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ (1967) and Jack Nicholson’s infamous road movie, ‘Easy Rider’ (1969). It is doubtful without the commercial success of Psycho any of these pictures would have been made.

Prior to the release of Psycho Alfred Hitchcock had a reputation as the ‘master of suspense without horror’. By blatantly displaying both nudity and violence (instead of subtle hinting at their presence as in his 1954 film ’Rear Window, for example) he had altered the perception to what is considered acceptable within cinema. Psycho is now considered as a yardstick for which all horror or thriller movies are measured. Although initially slated by some critics upon its release, one such report stated ‘with Psycho Hitchcock is simply attempting to lure us and make us jump through sudden acts of violence’ and another stating, ‘Psycho frustrates and reverses any romantic impulses towards clarity and fulfilment’, it is regarded today as a classic; a masterpiece of film making and a benchmark for other filmmakers to aspire to. Psycho influenced, amongst numerous other pictures ‘Dressed to Kill’ (1980) and Fatal Attraction (1987). Psycho is considered inspirational as it challenged the cinematic conventions of Hollywood from within the Studio System and proved undeniably successful. Hitchcock became known as a pioneer of the movement towards liberated filmmaking. The new tabooed experience of sex and violence inspired a whole new cinematic tradition and encouraged a whole host of directors to make pictures previously thought too explicit for cinema. Additionally, Psycho proved that the horror genre was indeed popular and capable of drawing in vast sums of revenue for Hollywood. Audiences took pleasure in being lost in the narrative of the picture. The chilling score by Bernard Herrmann only seemed to cement the tension absorbed. The film took the audience on a succession of visual and auditory shocks and thrills. Their reactions ranged from gasps of horror, screams, yells, to fleeing the cinema in terror. Today Psycho is considered a masterpiece, with arguably the most recognisable score, the most memorable scene (Marion Crane’s death), most memorable setting (The Bates Motel) and two of the most memorable characters (Norman Bates and Marion Crane). Hitchcock had indeed made his mark. However, in 1960 another British film – maker was attracting widespread acclaim in Hollywood.

Stanley Kubrick originally a photo journalist, had directed only one full length motion picture,’ ‘Paths of Glory’ (1957), to widespread acclaim before taking over the helm of Kirk Douglas’s increasingly troublesome historical drama project – ‘Spartacus’. Douglas, having fired the previous director, Anthony Mann, with whom he couldn’t agree with his visualisation of Spartacus, assumed the young director would be permissive to his point of view. The film was based on the 1952 novel by Communist writer Howard Fast about the Gladiator who led a rebellion of slaves against Rome in 73 B.C. Although Douglas was none too fond of Kubrick, (William Woodfield stated that Douglas referred to Kubrick as an ingrate, his creative talent did not go unnoticed by Douglas who hired him for a fee of 150,00 dollars. Kubrick had a clear vision for the picture; he wanted to make this the most realistic of all epics, totally unflinching in its depiction of war and a worthy successor to ‘Paths of Glory’ (1957). It was stated that make up man, Bud Westmore was given a completely free reign to create the most gruesomely brutal effects possible. As in ‘Full Metal Jacket’ (1987) this looked like an attempt to turn people off war. Kubrick had a clear intention as to all the visual aspects of the film. In what was to become synonymous with his lengthy career he was already demonstrating the meticulous attention to detail involved in his film making process, even going as far as to cast actors with physical deformities to portray the wounded in battle. These even included the casting of an actor with a part of his head missing to play one of the wounded. He scoured those lists of actors with limbs missing and other deformities to create adequate visualisations of the injuries sustained in battle. Kubrick even went as far as to use actual animal intestines and other insides when depicting those wounded in battle. Preview audiences were so disgusted with those maimed that all but one was removed. Spartacus was to have a sense of brutality and realism never seen before.

As the producer of ‘Spartacus’ Kirk Douglas took the lead role. However, the picture was credited with an ensemble cast including some of the most distinguished actors of their generation. Peter Ustinov, actor, playwright, novelist and thespian, Sir Lawrence Olivier and Charles Laughton. Kubrick relished the opportunity of working with such esteemed company and his direction suited their acting style. Sir Peter Ustinov was especially pleased as Kirk Douglas later reflected ‘Stanley let Ustinov direct all his own scenes by taking every suggestion Peter made’. It was additionally during the production of Spartacus that Kubrick began to experiment with the use of music to set the scene for the actors. The technique was used successfully in silent films to set the scene for the actors and Kubrick sufficiently employed this method during the production of Spartacus.

Kubrick, as a filmmaker believed in capturing every shot to perfection, this often meant twenty or thirty takes until he was satisfied. This attitude often infuriated those he was working with including Douglas and Russell Metty, the Director of Photography for Spartacus, but allowed Kubrick’s visual creativity to run wild. In late summer of 1959 the unit moved to Spain to shoot the battle scenes that Kubrick supervised. Kubrick had already endured numerous conflicts with Kirk Douglas over the state of the script and although no scenes depicting battle existed in the script Kubrick was insistent upon a set piece showdown arguing successfully that the audience would feel cheated without one. Calder Willingham was called in to script it and immediately decided to draw inspiration from Roman History especially that of Appian of Alexandria, a Greek born historian who wrote during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. From these sources Kubrick and Willingham erected a climatic confrontation incorporating the visual style Kubrick desired. The confrontation itself is absurdly and awkwardly directed, with Douglas at the centre of the action, and a plethora of improbable horse falls and clumsy stunt action. However, Kubrick had a trump card. It was his shot of the battlefield littered with corpses with Crassus and Julius Caesar strolling among the fallen, looking for Spartacus that enveloped his creative vision. It completely depicted Kubrick’s aversion towards war in a more powerful way than violence ever could.

Geoffrey Shurlock, head of the Legion of Decency’s Production Code Authority or Hollywood’s self censorship office had reservations concerning the initial content of Spartacus. The sexual overtones, as well as the violence depicted were his primary concerns. During postproduction Kubrick was ordered to make numerous cuts. Lawrence Oliver, the distinguished British actor hired to play Crassus, was involved in one particularly controversial scene in which he was noted in attempting to make a pass at Spartacus whilst bathing him. Kubrick is quoted as having intended the behaviour of Crassus to demonstrate an overtly homosexual advance, however the scene itself was dropped, not for its nature but for reasoning that it contributed nothing to the story. (The bath scene itself remained in print and approved by British censorship only to be removed, somewhat mysteriously, before general release.) However the legacy of Spartacus’s reputation has endured even to this day, with the film cited by many prominent homosexual men whom feel that its content contains undeniable homosexual undertones. In 1960 audiences were on the cusp of embracing liberalism, however there was also clear-cut guidelines towards censorship. Violence was the most noticeable concern for acceptability. With Kubrick’s vision of wanting to direct the most realistic depiction of violence ever committed to film, he was always going to encounter difficulties with censorship. Preview audiences were so appalled by the scenes involving maimed extras, all but one was removed. Geoffrey Shurlock was also concerned at the moment, during Spartacus’s crucifixion when Varinia begs him to die. This could be interpreted as suicide or euthanasia he argued. The scene was eventually cut, as was one which showed Spartacus hacking off a mans arm and one of Laurence Oliver having blood spurted into his face during battle.

Upon its release in 1960 Spartacus was a resounding success. Kubrick was credited with taking a limping project complete with cantankerous stars and delivering a smooth and confident epic. Audiences flocked to see Spartacus making it one of the highest grossing films of 1960. Over forty years on, with numerous re releases on DVD and television showings it is considered a very accomplished piece of filmmaking firmly placed Stanley Kubrick on the Hollywood map, he was 32.

‘See it…if your nerves can stand it after Psycho’ was the advertising slogan for the re release of Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Rear Window’ in 1962. Based upon a short story by Cornell Woolrich it is a tale of suspense and high-tension drama, though perhaps not Hitchcock’s best-known picture (Psycho holds that mantle), it is generally acknowledged as his most accomplished. The central theme in the film is the act of voyeurism, which is the act of observing other peoples lives for personal or sexual gratification. Hitchcock believed there is a little of the voyeur in all of us, a fact that he establishes from the opening scene of the picture. The title itself even gives the audience a clue to the content, as our lives are windows to be viewed in on, or from.

Few who have seen Rear Window do not consider it a truly top-notch thriller. Even those who differ in opinion as to Hitchcock’s greatest film they acknowledge the power and tension is inherent in this picture. The story centres around L.B Jerffries (James Stewart), a top-flight photographer, who as a result of an accident that has left him in a leg cast, is confined to his upper storey Manhattan apartment. He takes to amusing himself by gazing out of his window at the adjacent building and its inhabitants and observing snippets of their lives. Some of them such as ‘Miss Torso’, a lithe young ballerina who struts around in various stages of dress and ‘Miss Lonelyhearts’ a forlorn spinster keep their curtains wide open, others, like a newlywed couple prefer to pull the drapes shut, leaving Jeffries only to smile wryly at their activities. After all they are vital and alive and Jeffries is confined and impotent.

The visual style of this picture is masterful, although the idea of the voyeur witnessing a murder was nothing new nor unique, the manner in which Hitchcock presents it is singular. (Throughout the entire picture the audience only see Jeff’s point of view.) The set-up is compelling visually we are given peeks into the rooms of Jeffries unknowing neighbours only seeing what Jeffries does. No interaction between Jeffries and his neighbours takes place, but through this visual technique we, as the audience become curiously engaged by their personal stories. Through the use of this visual style we feel as Jeffries does, paralyzing powerlessness and as Hitchcock builds the tension we become totally absorbed within the story. Indeed, when Lisa (Grace Kelly) breaks into the suspected murderer’s apartment, Lars Thorwald and he returns, the tension becomes unbelievable. By this point we are completely invested in the character of Jeffries and his utter terror for Lisa’s safety we feel exactly as he does utterly helpless and confined.

Male and female gender roles are paramount within Rear Window. The central character Jeff is unwilling to commit to a relationship with Lisa. He sees her as too perfect, too feminine, a challenge to his ultra masculine job, that of an action photographer. Lisa spends a vast proportion of the film holding the relationship together. His perception of her drastically changes when she assumes the more reckless, brave and stereotypically masculine role by venturing into Thorworld’s apartment to retrieve evidence of a crime. Indeed there is a complete role reversal when Jeff, knowing Lisa is in danger gasps and holds his hands to his mouth girlishly, as he fears for Lisa’s safety knowing she is snooping in Thorwalds’ apartment and he spies the suspected perpetrators imminent return. By the end of the film it appears that the role reversal is complete. Jeff, who has spent the vast majority of the film stamping his authority, refusing to commit to a long-term future with Lisa spurning her dreams of marriage and commitment, has relented. The final scene itself depicts the changed gender roles of the two central characters, Jeff left more helpless than before (after being forced out of a window by Thorworld) and Lisa now adopting a much more masculine and commanding role in their relationship as the protector and Jeff is only too happy too oblige. It is only when Lisa herself is sure he is asleep that she feels comfortable enough to relax and quietly read her fashion magazine.

Rear Window left a legacy in Hollywood that is almost incomparable. The subject of numerous re-makes, the latest being the made for television, starring the late Christopher Reeve as a quadriplegic who engages with a cat and mouse game with a killer. Celebrated director Brian de Palma has made his own versions of Rear Window. First in ‘Hi Mom’ (1970) a comedy in which Robert de Niro plays an amateur pornographer that uses his neighbours as his subjects, then ‘Sisters’ (1973) where Margot Kidder plays twins one of whom is seen murdering her boyfriend by a neighbour. More recently Woody Allen’s ‘Manhattan Murder Mystery’ (1993) has an almost identical theme where Allen and Diane Keaton suspect their neighbour of killing his wife for insurance money. Rear Window has also been the subject of parody by ‘The Simpsons’ (1989) in ‘Bart of Darkness’ in which Bart, confined to his bedroom with a broken leg is convinced his neighbour, Ned Flanders murdered his wife with hilarious consequences. In my personal opinion Rear Window is Hitchcock’s most accomplished work. The narrative structure flows perfectly engaging the audience in Jefferies dilemma and tantalising their perceptions of the central characters. Through the camera sizes and angles we are firmly placed in Jeff’s world and the singular manner in which the film is shot leaves the audience vulnerable and exposed giving Hitchcock complete power to manipulate our emotions as we have complete and utter investment in the protagonists turmoil. Rear Window is a picture film that highlights the then social issues and the moral consequences of voyeurism, in other words you just might see something you wish you hadn’t. Social behaviour and the moral consequences, whether it is observed by another or perpetrated by oneself was later to become a central theme in arguably Stanley Kubrick’s most notorious picture – A Clockwork Orange.

During the course of 1969 to 1970 there had been a major shift in Hollywood towards youth cinema. In the wake of ‘Easy Rider’s (1969) 16 million dollar gross on a 400,000-dollar budget, studios approved substantial funding for cheap movies with young directors. It was during this time that Kubrick became interested in adapting Anthony Burgess’s novel ‘A Clockwork Orange’ for the big screen. The novel was a cult classic set in the near future in Great Britain where eighteenth century squalor co – exists with twenty first century technology. Due to this harsh environment gangs of young men have evolved who roam around the streets free to assault, rape and even murder their fellow citizens for their own self-gratification. The story centres around one such gang, ‘the Droogs’, led by an intelligent fourteen year old who adopts the moniker ‘Alex De Large’. We follow the gang’s experiences until Alex is captured after a particularly vicious attack on a middle class couple. The story then centres on Alex’s re – education by way of aversion therapy, a top secret experiential procedure called the ‘Ludovico Technique’. It causes him to become nauseous at the thought of inflicting violence on anyone. Alex seems completely rehabilitated; the only side effect of the treatment being it has produced a loathing of his beloved Beethoven. Back on the streets Alex befalls a series of misgivings. He is attacked by tramps he once beat up, victimised by his friends who are now policemen and finally imprisoned by the husband of a woman he fatally raped, who seeking retribution plays Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony until he throws himself out the window.

Brutality, violence and its consequences are the central themes of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Hollywood’s shift towards a new wave of American cinema demanded previous taboos be challenged and he fully intended to show graphic violence, explicit sexual content and profanity. The attacks themselves visually are not shown in too much detail, in comparison with Sam Peckinpah’s films, ‘The Wild Bunch’ (1969) or ‘Straw Dogs’ (1971). Nonetheless the context in which violence is used is highly controversial. The fact that all of Alex’s victims are attacked without reason and our typically unable to defend themselves from both him and his ‘Droogs’ that is highly controversial. Audiences were used to rationalise the violence they view on screen by justifying it in their minds, but by portraying it in an irrational, unnecessary manner, the film seemed overly brutal. One particular scene, which has often courted the most controversy, is when Alex and his gang (Droogs) sexually and physically assault ‘the cat lady’ (Miriam Karlin). They break into her home, destroy her property, verbally mock her profanely, assault and subject her to multiple rapes all the while singing, laughing and joking. After this horrific ordeal Alex then murders her by dropping a giant phallic shaped object on her face. The brutality, sexual innuendo and violence in this scene are graphic. In my opinion, visually this scene is one of the most notorious in cinematic history. Along with the infamous ‘head spin’ in ‘The Exorcist (1973) it is one of the most disturbing scenes visually, ever committed to celluloid.

A Clockwork Orange is also powerfully homoerotic with multiple references to gay culture. Alex preening as he prowls around his parents’ flat in his underwear; touching his toes to accommodate the rectal examination of Michael Bates (the chief guard) or accepting with faux naïve innocence the sexual advances of ‘Deltoid’ (Aubrey Morris) and two fellow prisoners, to even his wearing of make-up and his doll like fake eyelashes. All of these instances give clear reference to gay iconography. ‘A Clockwork Orange’ showed Kubrick didn’t lack sexual imagination, it revealed a sensual side to his persona, which until then had only appeared fleetingly in his work.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s there was a social and cultural liberation upheaval,. A factor, which did not go unnoticed by artists. The somewhat conservative opinions which dominated the previous decades were considered antiquated and the public were embracing a more ‘free spirited’ way of thinking. Artists such as The Beatles and Led Zeppelin dominated the music charts and Andy Warhol’s creative visions were appreciated. The public seemed ready for A Clockwork Orange. Kubric’s visual design of the film was to be revolutionary. According to the Anthony Burgess novel the exact décor of the Korova milk bar, Alex and his Droogs main hangout, was ambiguous. Kubrick and John Barry, whom he’d chosen to design the film, saw it as a ‘temple of sexual consumerism’. Kubrick knew of London pop artist, Allen Jones who had caused a furore with three pieces of sculptural ‘furniture’ based on life sized mannequins of women in bondage harnesses. There was a fibreglass figure on all fours with a sheet of glass on her back, which became a coffee table and the same figure upright, which became a hat stand. Kubrick felt these would be perfect visual images for the Korova milk bar. When we are first introduced to Alex and his Droogs within this setting it is immediately evident that the milk bar is intended to be interpreted, visually as a shrine to sexual consumerism.

Warners released A Clockwork Orange in New York just before Christmas 1971. Whilst there was minor criticism concerning the level of violence, most people seemed ready to accept the film as a valid satirical comment. It was given the uncommercial X certificate barring minors from viewing the film. Initially, with the exception of a few minor criticisms A Clockwork Orange did not attract too much negative press attention. It was only with the release of Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Straw Dogs’ that critics acknowledged the increase in violence permitted on celluloid and the furore began. John Trevelyan, the chief British censor of the time saw more good than harm in the film and wrote,’ I think it is perhaps the most brilliant piece of cinematic art I have ever seen… in an age where violence is on the increase Kubrick is challenging us to think about it and analyse it.’ However, Trevelyan was able to acknowledge that not everyone will agree with his point of view. Among those whose opinion differed was Labour MP Maurice Edelman, who felt that A Clockwork Orange would lead to an increase of youth street crime. In fact, the term A Clockwork Orange had become used within the national press to describe anyone whom had fallen foul of teenage violence.

The controversy surrounding A Clockwork Orange has endured. The evidence it encouraged youth street violence is flimsy. However, there are cases of crimes, which draw stark contrasts with the film. A seventeen-year-old Dutch girl was raped in Lancashire by a gang chanting ‘Singing in the Rain’ as they did so. However, no reliable witnesses ever came forward. Kubrick promptly defended the film and the right to freedom of artistic expression. In March the film received four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director. But when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences approached stars to present the awards, many (including Barbara Streisand) refused to do so, or even attend the awards for fear of honouring such an infamous film. In the wake of all the controversy surrounding A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick remained an elusive figure rarely emerging from his Abbots Mead Mansion. In 1972 Florida newspapers announced that on moral grounds they would not carry on advertising A Clockwork Orange, a decision, which led to Kubrick’s withdrawal of the film from the state. Eventually after continued hostility and even death threats to Kubrick and his family he, with the support of Warners, took the decision to outlaw the film completely. In 1971 it was unheard of for any director to enforce a boycott of their own picture, a testament to the influence this picture gartered. The subject of extreme violence and morality would feature again in Kubrick’s work and it was never more predominant than his adaptation of Stephen King’s ‘The Shining’.

“I’m the Devil, now kindly undo these straps!” Few who have seen William Peter Blatty’s ‘The Exorcist’ (1973) have ever forgotten it. It remains one of the most truly terrifying motion pictures of all time, a fact that was not lost on Stanley Kubrick. Warners had already offered him the opportunity to direct a sequel, which he wisely turned down; the film was a complete failure both critically and commercially. The proposal had stuck in his mind though. As early as 1966 he had confided in a close friend his desire to make the ‘scariest movie of all time’.

Having recently being handed a novel by a young author, Stephen King called The Shining which he identified with, and seeing the commercial success of Brian de Palma’s ‘Carrie’ (1976), another Stephen King novel, Kubrick felt the transference of this story into film would potentially prove a critical and commercial success.

The book tells the story of the moral and mental deterioration of Jack Torrance, a man assigned as the winter caretaker of The Overlook Hotel. A sullen former teacher and alcoholic with literary ambitions Torrance had taken the job in hope of finishing his first novel. However once he, his wife and young son are alone in the hotel its spirits begin to affect him, as they had the previous caretaker, culminating in him attempting to slaughter his family.

Kubrick’s vision of The Shining differs from that of its author Stephen King. Whereas King saw it as more of the possession of spirits within the house driving Torrance to commit these atrocities, Kubrick felt the examination of one man’s descent into madness by an overbearing wife and difficult and demanding son, a much more interesting concept.

‘The only epic horror film’ is perhaps the best way to describe The Shining. It incorporated a visual style not seen before within the genre. Central to the story of The Shining is the breakdown of Sam Torrance, portrayed brilliantly by Jack Nicholson. The acting performance is of such quality that as a visual point of reference it is impossible to take your eyes of him. One of the most iconic visual images in cinema is that of a homicidal Jack Nicholson smashing the bathroom door with an axe and then bellowing “Here’s Johnny!” to a petrified Shelly Duvall. Patrick McGilligan in his autobiography wrote, ‘His hair became mangier than Henry Moon’s, his eyes zoned out; his tongue lolled around inside his mouth…Jack seemed to enjoy the murderous mood. He couldn’t resist a hint of comedy, playing the madness like an ape, grunting, muttering and swinging his arms from side to side as he lunged down empty corridors.’

The visual characteristics in The Shining are quite breathtaking. Kubrick knew he needed to create a sense of isolation, as the story demanded it. He achieved this through long and wide panoramic shots of the hotel. In contrast with the technique employed in the visual style of other horror films where the audience identifies the situation through claustrophobia, as in ‘The Exorcist’ (1973), the visual technique used by Kubrick is exactly the opposite.

The purpose of a horror film is to scare and shock an audience. Kubrick knew that in order to leave an indelible psychological imprint on the audience he must tap into those nightmarish scenarios buried deep within our subconscious. He employed a ‘camera chopping’ technique to make the audience jump, by luring them into a false sense of security. This is shown with Danny’s ‘shining’ with shots of horrific murder and supernatural imagery interlaced together in quick succession.

Some of the most startling images in contemporary cinema occur in Kubrick’s The Shining. Whether it was the elevator door sliding open to disgorge a flood of blood, the nude girl who rises from the bath and embraces Jack, only to turn into the rotting corpse of an old woman, or the apparent scenes of homosexuality including two men in animal suits surprised in a hotel room during an intimate moment, it is certain that Kubrick wanted The Shining to be one mass of nightmarish hysteria.

The Shining was released on Friday 13th June 1980 and broke house records at six cinema venues. ‘Newsweek’ called it ‘the first epic horror film, a movie that is to horror movies what 2001: A Space Odyssey was to other space movies.’ Its overall commercial success was greeted with lukewarm critical response. Variety savaged the film and Jack Nicholson’s performance. Stephen King disowned it. But by the year’s end it had made Variety’s list of the top ten money-makers of 1980 and is even revered today as a masterpiece of modern horror, recently topping a poll on Channel 4 as the scariest movie of all time. Kubrick had created an undeniable piece of cinematic history once more.

The collective contribution of the works of Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock upon contemporary cinema could not have been greater. As writers, producers or directors their pictures are considered masterpieces. The movies of both directors are visual feasts with vast social connotations. Collectively their works have influenced generations of actors, directors, producers and writers. With Psycho and The Shining often vying for the title of ‘the greatest horror film of all time’, A Clockwork Orange considered as the most controversial movie ever made and Rear Window the subject of numerous re-makes, the collective legacies these pictures left have influenced generations of directors, actors and producers as well as entertained audiences for over forty years.

As previously stated both directors had very bleak views on society. This is reflected within their works. They in term raise similar social issues. In A Clockwork Orange Kubrick examines our social, or in this case anti social behaviour and looks at its consequences. In Rear Window Hitchcock examines social behaviour, more specifically voyeurism and examines the consequences of this act. Both of these acts can be considered repulsive and morally wrong, however the outcomes of these pictures are coincidentally similar, but have very different messages. In A Clockwork Orange the lead character commits suicide by throwing himself out of the window, whereas in Rear Window the protagonist, Jeff is forced out of the window by the perpetrator of the crime. In both of these films the audience is made aware that malevolent characters exist within our society.

The visual styles of both directors were different. Kubrick, for example preferred wide shots often with the camera placed along one side of a wall as on ‘Full Metal Jacket’ (1987) or the hotel corridors in The Shinning (1980). Kubrick also favoured close up shots of intensely emotional faces. This is well displayed in ‘The Shinning’ when we see numerous shots of all the actor’s faces, mostly portraying the distress of the situation. Hitchcock’s approach in the majority of his pictures was different. As in ‘Rope’ (1948), ‘Dial M for Murder’ (1954) and Rear Window (1954) the story evolves in a singular location. This being the case the camera shots are much more singular, a sense of claustrophobia is felt by the audience.

Both Kubrick and Hitchcock both encountered controversy with their pictures. As I have previously stated A Clockwork Orange was banned for more than twenty years and was withdrawn from the cinema by Kubrick himself. Whereas Psycho provoked hysteria upon release, with real life serial murders claiming its influence for their crimes and sociologists claiming Psycho could be held accountable for all manner of events, from a rise in crime and violence, to the decline in motel stays, the decline in sales opaque shower curtains and perhaps, most bizarrely a recognised social phobia of showering.

In summary, the films of Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock incorporate distinctive visual styles, have far reaching social connotations and are revered in today’s modern culture as yardsticks’ for other filmmakers to aspire to. Twenty-six years after Hitchcock’s death and almost ten since Kubrick’s passing, their collective legacies are cemented.

'You may call me Mr Hitchcock'.

‘Stanley Kubrick is a talented shit’ – Quotation – source: Stanley Kubrick – A Biography by John Baxter.

……..’Hitchcock placed ‘Mrs Bates’ in actress Vera Miles’ dressing room to test its ‘scare factor’ – Quotation – source : www.imdb.com trivia section for Psycho.

‘Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest, most shocking mystery with a galaxy of stars’ – Quotation – source : ‘The Complete Hitchcock’ – Paul Condon and Jim Sangster.

‘Hitchcock is simply attempting to lure us and make us jump with sudden acts of violence’ and ‘Psycho frustrates and reverses any romantic impulses towards clarity and fulfilment’ – Quotation – source : ‘The Complete Hitchcock’ – Paul Condon and Jim Sangster.

‘Wiliam Woodford stated he refered to Kubrick as an ingrate’ – Quotation – source : Stanley Kubrick – A Biography – John Baxter.

‘Stanley let Ustinov direct all his own scenes……. Quotation – Source : Kirk Douglas –The Ragman’s Son.

‘Geoffey Shurlock, head of the Legion of Decency’s Production Code Authority or Hollywood’s self censorship office had reservations concerning the initial content of Spartacus’ – Quotation – source : Stanley Kubrick – A Biography – John Baxter.

‘See it if your nerves can stand it after Psycho’ – Quotation – source : ‘The Complete Hitchcock’ – Paul Condon and Jim Sangster.

8’Hi Mom, ‘Sisters’ and ‘Manhattan Murder Mystery’ Quotation – source : The Complete Hitchcock – Paul Condon and Jim Sangster.

‘During the 1960’s and 1970’s there was a social and cultural liberation upheaval’ –Quotation – source : A History of the Cinema from its Origins to 1970 – Eric Rhode.

‘……….Allen Jones who had caused a furore with three pieces of sculptural furniture based on life sized mannequins of women in bondage harnesses’ – Quotation – source : Stanley Kubrick –A Biography – John Baxter.

‘ I think it is perhaps the most brilliant piece of cinematic art I have ever seen….in an age where violence is on the increase Kubrick is challenging us to think about it and analyse it’ – Quotation – source: Stanley Kubrick – A Biography – John Baxter.

The cases of crimes that draw contrast with the themes of A Clockwork Orange are examined in Stanley Kubrick – A Biography – John Baxter.

“I’m the Devil, now kindly undo these straps!” – Quotation – source : The Exorcist (1973) scene where Father Merrin knowing Regan is possessed asks who is it whom has possessed her, taken from my knowledge of the film.

This blog’s great!! Thanks :).

| Posted 15 years, 1 month ago